I was born in 1972 on Moody Air Force Base in Valdosta, Georgia — a place that sounds like the start of a Tom Clancy novel, but mostly involved mosquitoes, humidity, and dads with military haircuts. Mine was stationed there, doing Official Air Force Things while I was busy being a very tiny person with zero clearance.

My early childhood base of operations was a glorious, sun-bleached, not decrepit at all white single-wide trailer, retrofitted with all the essentials: shag carpet, dented toy box, and a mysterious smell that might’ve been the ghost of a grilled cheese. Eventually, we upgraded to a double-wide trailer, which to my young mind was the equivalent of moving into a space station. A space station with rattlesnakes, because it was parked on Totem Pole Ranch, a working Paso Fino horse farm where my parents wrangled horses and I mostly dodged venomous reptiles like some sort of toddler Indiana Jones.

The ranch had horses, goats, chickens, and the occasional guest appearance by death via fang. The soundtrack of my youth was a chaotic symphony of whinnying, clucking, hammering, and a grown man yelling, “WHERE’S THE RAKE?!”

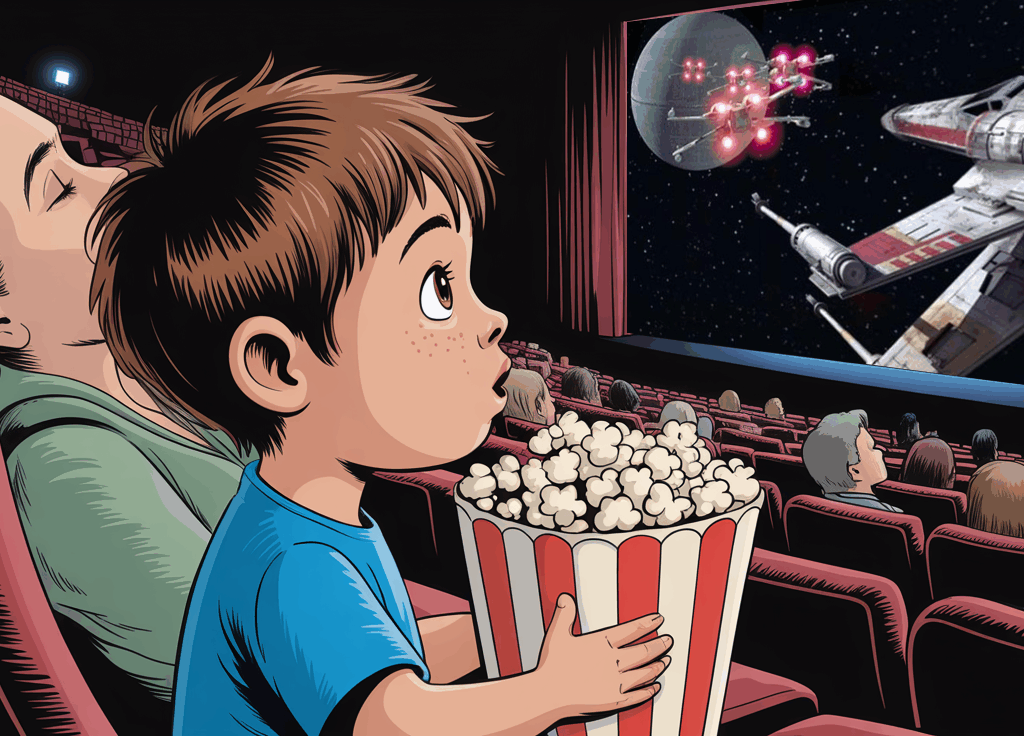

But then something galactic happened.

1977. A little film called Star Wars hit theaters, and I saw it in the theater. That’s right. Episode IV. Big screen. Lights went down. The crawl rolled. My jaw dropped. My mom fell asleep. Unforgivable. I, on the other hand, was transformed on a molecular level.

For years afterward, I spent my afternoons outside in the dust, throwing dirt clods at each other and narrating full-blown X-wing vs. TIE-fighter battles with dramatic sound effects that were mostly just me yelling “PEW! PEW!” at maximum lung power. I was Rogue Leader. I was every droid. I was the rebellion.

But in 1980, the Empire struck back in the form of a move to Kansas. Specifically, Fall River — a town with more tumbleweeds than people. We stayed for six months before my parents wisely decided that perhaps “frontier ghost town” wasn’t a great vibe and moved us to Grantville, Pennsylvania, which had slightly fewer tumbleweeds and significantly more cows.

There, my dad and Pop-Pop teamed up to sell Rainbow Rexair vacuum cleaners. These things were like reverse ghost traps — clunky, powerful, and vaguely capable of extracting your soul if you used the wrong setting.

But my parents never could shake Horse Fever, so in sixth grade, they went full equestrian again and bought a farm — officially dubbed the New Day Equestrian Center, home of the Capital Area Therapeutic Riding Association. The place was alive with horse therapy, horse shows, chickens, cats, dogs, guinea pigs, regular pigs, goats, rabbits doing rabbit things and horses doing horse things, like stepping on your foot and judging your outfit.

And me? I was… indifferent.

Sure, I could ride. I could muck a stall. I could out-shovel the best of them. But in my heart I was living in another galaxy, gripping an Atari joystick and waiting for my E.T. cartridge to work (it eventually did and I’ve regretted it ever since). I was a card-carrying Atari Club member. Horses were fine, I guess, but they didn’t blink or make satisfying beeps when you plugged them in.

Where I did align with my parents — or at least with my mom — was music. I started in second grade and never looked back: cello, piano, drums. If it made sound and required hauling awkward gear into awkward places, I was into it. That path led me to Millersville University, where I majored in music education with a focus on cello — the giant wooden instrument that makes you feel sophisticated and vaguely medieval.

So naturally, upon graduation, I went straight into tech support. I just didn’t feel… old enough… to be a music teacher. Maybe I could’ve learned that sooner, but whatever. I have not once regretted it. I’m not sure there’s a more rounded education that you can get than a music ed degree, and it’s served me well.

Anyway, it was the 90s and I had too many flannel shirts, more ambition than sense, and bills. I landed at MindSpring, doing dial-up tech support, which mostly involved saying, “Try unplugging it and plugging it back in,” and trying not to sing along the thousandth time I listened to somebody’s 56K modem scream like a haunted fax machine.

Eventually, I joined the tech writer team, where I translated things like “What does the Home button do?” into engrossing help docs for apps like Eudora, Mosaic, Netscape, Telnet, and Gopher. (If you remember Gopher, hit me up on IRC.)

In 2005, I moved to Atlanta, became a product manager at EarthLink, and began the sacred ritual of saying “no” to people asking for absurd features they thought would only take “like half a day.”

From there, I joined a startup called Vitrue, where we built a social media management app back when Facebook still had poke wars. We got acquired by Oracle, where I helped glue software systems together using hope and vague documentation.

After three years, I paused for a breather. Moved to DC, started a family, and welcomed our son, Hugo, in 2017. He’s perfect. Like, final-form Pokémon perfect.

Then came Vaudience, a startup I founded to collect real-time feedback at live events. It was going great until the universe said “global pandemic!” R.I.P. Vaudience.

But the skills I honed building Vaudience were perfect training for my next gig: VP of Product at Accelevents — an all-in-one platform for running both in-person and virtual events. Since 2021, I’ve been riding that rollercoaster, solving weird problems, learning things I didn’t expect to learn, and occasionally muttering, “This wasn’t in the Jira ticket.”

Meanwhile, music has remained my constant. Since 2001, I’ve been part of Song Fight, a weekly online songwriting competition where you write a brand-new song based on a weird prompt. I now help run the thing and plan to keep going until my ears retire or my fingers fall off, whichever comes last.

Most recently, I’ve been obsessed with generative AI — this wild, barely house-trained technology that lets you generate text, images, music, and vibes using your computer. It feels like the early internet again: chaotic, full of promise, and possibly about to explode.

I’m using AI to amplify my art, my writing, my music — all the weird stuff I’ve ever loved, now with robot assistance.

We’re at the beginning of something big, and while it’s totally valid to feel a little freaked out, I’m choosing hope. As Rebecca Solnit says, the dark unknown can be where hope lives. And I’m totally here for it.

If you’re curious about music, tech, weird AI stuff, or what happens when you throw a dirt clod at a snake by accident — reach out. I love talking shop.